One for the Highers here – and linked quite closely to my own research. Intermolecular forces.

Believe it or not, you will have encountered the effects of these forces everyday of your lives. They are the reason why certain chemicals dissolve in water, and why others don’t; why water expands upon cooling, whilst most other liquids contract; why geckos and spiders can walk on walls, but you cannot.

These forces work at the molecular scale but have a profound impact on much bigger things which we can observe.

One key area which pupils have the most difficulty in understanding, is that these are not bonds; and changing state doesn’t always involving bond breaking. Despite the strongest among them being called “hydrogen-bonds” there are no bonds formed in the interactions. They are just that – interactions.

First let’s take the example of a material with extraordinary strength – diamond. Diamond is made of pure carbon (though small impurities can be present which give the diamonds colours – traces of nitrogen, for example, gives diamonds a yellow colour, boron gives them a blue colour, whereas deformities in the structure caused by impurities yields red or pink diamonds). The reason for diamond’s strength lies in its covalent bonds. These are between each carbon atom in its structure. Carbon has four bonds in a tetrahedral arrangement, so each carbon bonds to four neighbouring carbon atoms. This is repeated billions of times across the entire material. If you want to melt diamond, you will have to break each of these billions of highly stable and strong bonds, which requires a significant amount of energy. Under normal conditions, diamond won’t melt anyway – it turns into graphite, then it sublimes – that is, it goes straight from a solid to a gas at a temperature of around 3915°C. These bonds are intramolecular forces – they occur within the structure of the material, holding the atoms together. Since diamond is made from interconnected atoms all bonded together, a single diamond is, from a certain point of view, one single molecule. There are other forms of carbon known – graphite, fullerenes, graphene to name a handful – and will be discusses in later article.

Intermolecular forces occur between molecules on the other hand, are not bonds. An intermolecular force acts a little bit like a magnet (though it is not related at all to magnetism! This is merely a useful analogy – magnetism is something else entirely – useful, but sometimes unhelpful, as some pupils wrongly assume it to be magnetism!). On the small scale, two neighbouring molecules have features in their structure that attracts one to the other in a weak interaction.

The interactions are classified (at Higher level at least) into three distinct types, the weakest two being the Van der Waals forces.

London dispersal forces

The London dispersal force is the weakest of the three intermolecular forces. This one is driven by pure chance – that of how likely it is for the electrons in an atom to be randomly located more on one side than the other. This force is present in all molecules, but the Noble Gases form an excellent and elegantly simple example of how they arise. Remember that the Noble Gases are not molecules – they are free, very unreactive atoms. Electrons are orbiting their atoms constantly. If we were to stop time, we would potentially observe that the electrons are, by chance, evenly spaced out. On the other hand, we might also notice that there may well be a greater electron distribution on one side of the atom than the other.

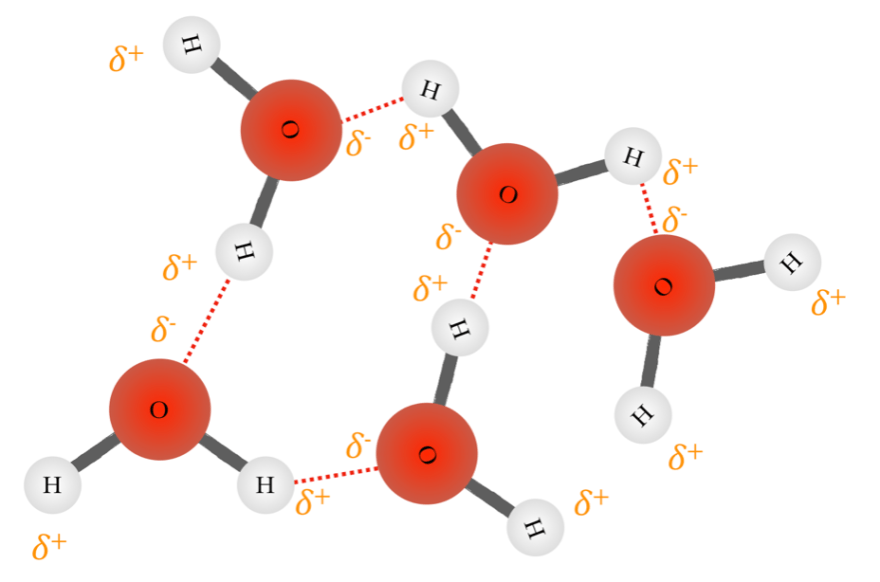

Electrons, possessing as they do a negative charge, cause the atom (helium or xenon perhaps) to be slightly more negatively charged on one side than the other. The side where electrons are currently less abundant will have a slightly positive charge. These charges are temporary, as the electrons are in constant motion, it is not like an ionic charge which is permanent. As such we refer to these temporary charges as a temporary dipole and we give them the symbols 𝛅+ for a positive dipole, and 𝛅– for a negative dipole.

If the atom is left undisturbed, the electrons continue to move around it randomly and the dipole will disappear and reappear and reorient continuously. If, however, there is another neutral atom nearby (such as helium for example), something rather interesting happens. The dipole in the first atom induces a dipole in its neighbour. This means that the negative dipole in the first atom repels the electrons in its neighbour, so they move to the opposite side and it forms a induced dipole. The opposite is also possible – the positive dipole in one atom can draw the electrons in a neighbouring atom towards it, inducing a dipole too. This induced dipole means that a positive dipole in one atom and a negative dipole in another are now attracting one another – exhibiting a weak intermolecular interaction – a force of attraction known as a London Dispersal Force.

To return to the magnetism analogy again, this is very much like placing two bar magnets next to one another – one will spin so that the north pole of one points to the south pole of the other. Opposites attract! Here we are causing a similar phenomenon to occur with the electron in a pair of atoms (but it is NOT magnetism!).

This phenomenon is not unique to individual atoms of Noble Gases, they also occur between molecules (the Noble Gases above were selected as they make a simple example).

The London Dispersal Forces are the weakest type of intermolecular interactions. Some might go so far as to call them pathetically weak, however, they can have a profound impact on nature should they build up. The same process happens in the tiny hairs in a spider or gecko’s feet – interacting with the molecules in walls and ceilings to create a force strong enough to hold them together. The lightness of these creatures, combined with the many millions and millions of hairs undergoing these interactions, adds up to allow them to suspend their weight against the force of gravity.

Permanent dipole – permanent dipole interactions

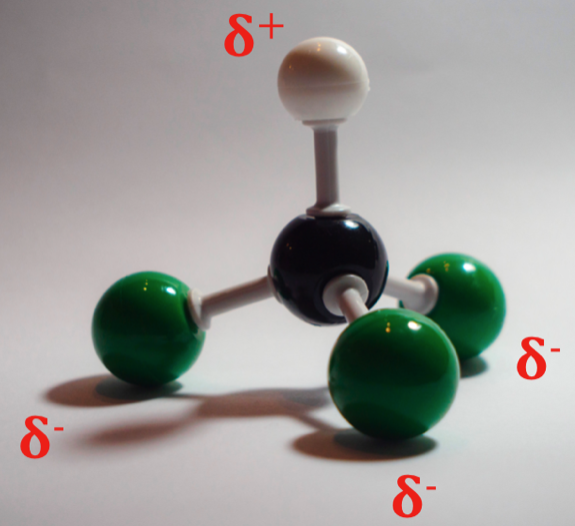

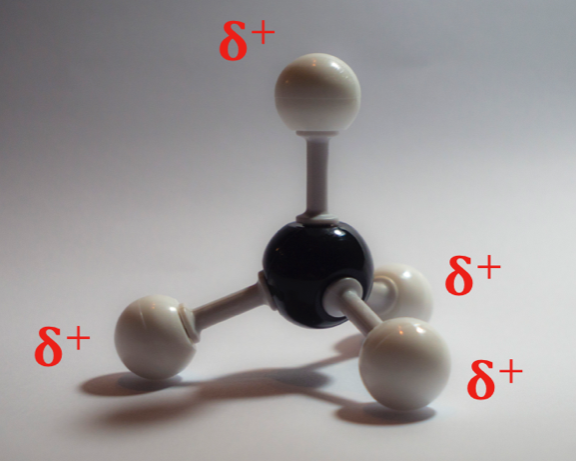

A permanent dipole is one which is not induced – it is there permanently. This is caused by a difference in polarity between two atoms in a bond. Let us take chloroform as an example – CHCl3. To establish if a bond is polar, we investigate the electronegativity of each atom. Carbon has an electronegativity of 2.5 on the Pauling scale, hydrogen has 2.2, and chlorine has a large electronegativity of 3.0. There is not much difference between the carbon and hydrogen atoms – 0.3, so carbon is slightly more electronegative. This means that the electron density on the molecule is less around the hydrogen, and more centred around the carbon. However, chlorine is really electronegative compared to both the carbon and the hydrogen. This means that electron density is being pulled more towards the chlorine atoms than anything else.

As such, one side of the molecule will have more negative charge than the other – the side with the chlorine has permanently negative dipole – the hydrogen side has a permanently positive dipole. There will of course be some random fluctuations in electron density from the London Dispersal Forces, however this will be almost negligible compared to the power of this permanent dipole.

When a molecule of chloroform is next to another molecule of chloroform, they orient themselves to line up their dipoles. Opposites attract! The positive dipole in one molecule interacts with the negative dipole in the other and an intermolecular force is generated. Consider if you will a similar molecule – methane. Methane has the formula CH4 – it is identical to chloroform, but for the fact that chloroform’s three chlorine atoms are replaced with hydrogen atoms. As such, methane cannot exhibit any permanent dipole interactions. Methane boils at around -162°C – it is a gas at room temperature. It can form a liquid however, and can even be frozen solid at -182.5°C. This is because at these temperatures, the motion of the molecules is slow enough that London Dispersal Forces can take effect. Chloroform on the other hand, boils at 61.2°C, meaning that it is a liquid at room temperature. The permanent dipole in chloroform draws the atoms together much more easily and with greater force than in methane, allowing it to be stable as a liquid at such a high temperature compared to its hydrocarbon cousin.

Not only does this provide an interesting difference in melting and boiling points, but it also makes chloroform very useful. Chloroform is an excellent solvent for polar compounds. Its permanent dipole means that it readily solubilises other polar compounds. I make use of it on a daily basis in my research. If I am cleaning glassware that has held molecules with polar structures, I will rinse it with chloroform (as well as a combination of other polar solvents, such as methanol, acetone, and dichloromethane) in order to dissolve them. When I analyse molecules with NMR (nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy – I will write a post on this later as it is truly fascinating!) they have to be in solution. If the molecule is polar, I often use deuterated chloroform. This is the same as regular chloroform, however its hydrogen is replaced with deuterium – hydrogen’s heavier isotope (remember them from National 5?) – heavier by one neutron. This still has the polar, permanent dipole properties of regular chloroform, allowing it to dissolve polar compounds, but the deuterium being NMR inactive, prevents the solvent from showing up in the spectra and potentially spoiling it. It acts as an NMR invisible solvent.

You might have heard stories where chloroform is used as a knock-out chemical (James Bond and the Famous Five two notable examples) – it is particularly adept at this as it evaporates easily (having a much lower boiling point than water) allowing it to be inhaled by the victim. Whilst permanent dipole – permanent dipole interactions are stronger than London Dispersal Forces, this lower boiling point than water is explained by the next type of intermolecular interaction.

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonding is NOT BONDING! This is a common misconception amongst pupils because of its name… The reason it is called hydrogen bonding is because the interaction involves hydrogen, and is the strongest of intermolecular forces, strong enough to be comparable anecdotally to covalent bonding in some cases, but in reality, it is no way near as strong.

I think perhaps water is responsible for this misconception, as it is so often the best example of hydrogen bonding that one can relate to.

Hydrogen bonding occurs thanks to extreme polarity in molecules, often caused by a limited number of functional groups. These involve the hydroxyl group, -OH, amine, -NH, and hydrogen fluoride, H-F. If you are questioned as to what type of intermolecular force a molecule might exhibit, always look for these three bonds. If they are present, then the most dominant forces are almost exclusively going to be hydrogen bonding.

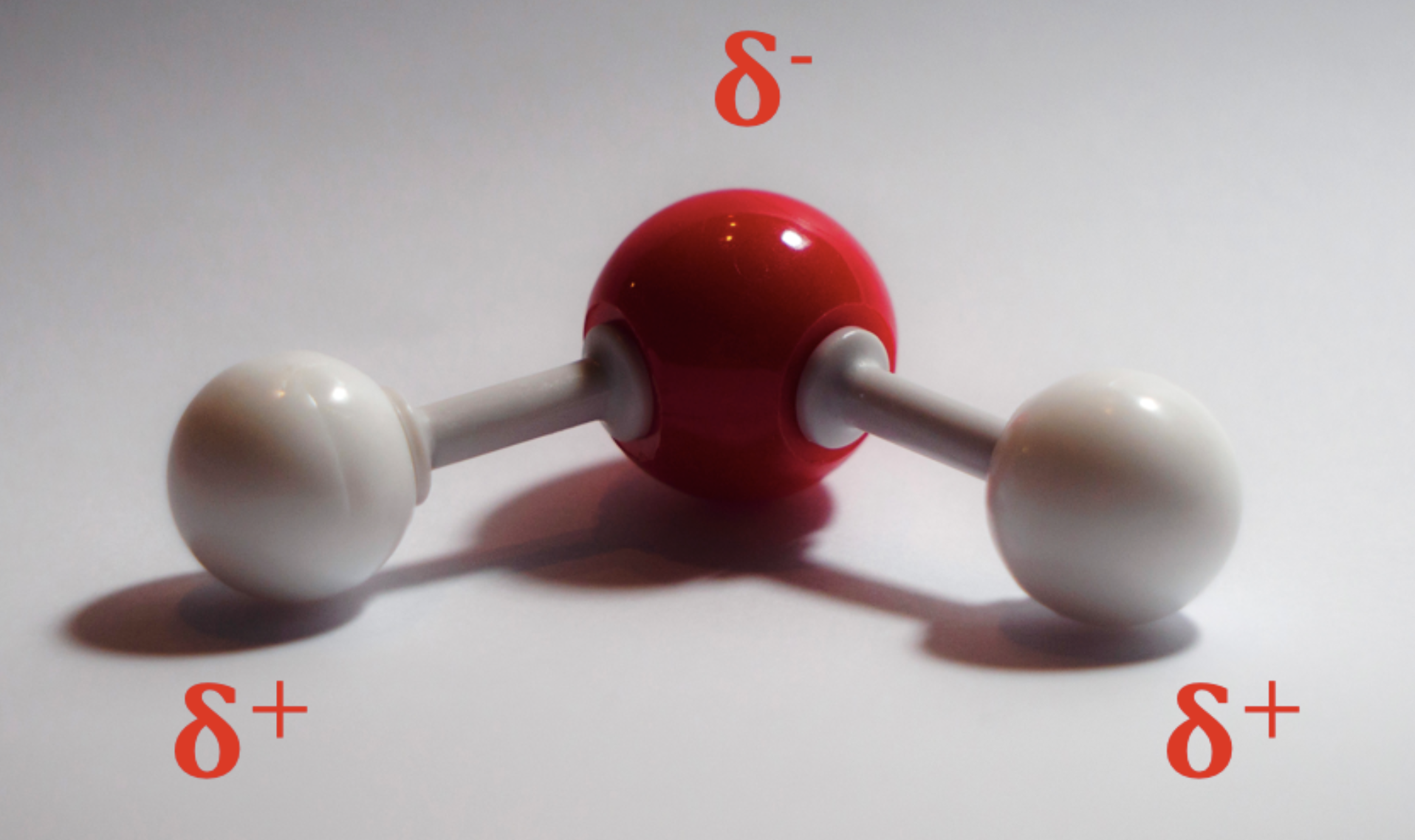

As I mentioned before, a common case study is that of water. H2O, H-O-H – from its structure alone it is clear that hydrogen bonding must be present.

Let’s look at the polarity of the bonds. Hydrogen has an electronegativity of 2.2 on the Pauling scale, whereas oxygen has 3.5. The molecule’s shape is bent, or angular, meaning that there can be no pure 360° symmetry, so there is a permanent dipole. Water molecules therefore undergo permanent dipole – permanent dipole interactions with their neighbours. Since the difference in electronegativity is so large (and it involves hydrogen) these permanent dipole – permanent dipole interactions are called hydrogen bonds.

Water boils at 100°C, which is much higher than similar sized polar molecules – ammonia, NH3 for example, boils at -33°C. In the liquid state hydrogen bonding is so powerful compared to weaker interactions, that the boiling point is extended so high in water. This is the reason that most lifeforms are water based. Without this property of water, life (as we know it) could not possibly exist on Earth. Another point about water is that it expands upon freezing, unlike other compounds which contract. If you have ever put a plastic bottle full of water in the fridge (or any water-based drink in a sealed container for that matter) then you probably noticed that the container burst when it froze. The reason for this is that in the liquid state, water molecules are free to flow around one another like any other liquid. When liquid mercury freezes, the metal atoms orient themselves into a regular array, taking up as little space as possible. In water, the hydrogen bonds occur between each molecule, and the molecules line up so as to maximise these strong interactions. What results is a large porous structure, where molecules are not stacking as close together as with metals and other compounds.

Think of this example as analogous to all the pupils in your school being put into the gym or assembly hall. As a liquid, pupils are not connected in anyway, and can move closer together as they walk past one another. In the mercury example, there no hydrogen bonds, when we freeze the pupils, they will stand as close together as possible, lined up in rows. Depending on the size of your school, this will probably take up between a quarter to a half of the room. Now let’s say that pupils exhibit hydrogen bonding. In this case when we freeze them, all pupils must line up as best they can whilst holding hands with arms outstretched at 109.5° in front of them with no bend in the elbow. This means that, like water molecules, there will be more space between each pupil, and much more of the hall will be taken up by people.

An additional point of note which I should add with respect to my statement of hydrogen bonding not actually being a type of bond. This is true, but in addition to being an intermolecular force, hydrogen bonding can also be an intramolecular force – that is it a functional group in a molecule can interact with another part of the same molecule or compound. This leads to it impacting the crystal structures of some compounds (organic-inorganic hybrid perovskites can exhibit hydrogen bonding between the A cation and halides in the BX3 octahedra), as well as causing some more complex molecules like proteins and enzymes to fold and maintain specific shapes to interact with specific chemicals. Why does a protein denature when in a different pH? Because the effects of hydrogen bonding are negated and the structure can unfold, rendering it useless.

An example of this you may be familiar with is with coffee. Some say that all true scientists live on coffee, a beverage I have a particular predilection for myself. If you drink a lot of proper coffee, involving frothed milk (the physics and chemistry surrounding the formation of microbubbles will have to be something to discuss another day!) such as latte and cappuccino, you may notice that you often do not need to use sugar. Without frothing, the coffee is bitter and is often enhanced by application of sucrose crystals if you have a sweet tooth, but when frothed correctly by an experienced barista, the milk takes on a sweet flavour, requiring no additional sugar. One reason for this lies in the molecules in the milk itself. At higher temperatures, the proteins therein denature, unravelling due to the strengths of the hydrogen bonds being overcome at higher temperatures; and producing a significantly different taste. Additionally, the natural carbohydrate lactose in the milk (a type of sugar) becomes more soluble in water at higher temperatures (its hydrogen bonding with the water molecules increases) and produces a sweeter taste when in contact with the tongue. I should point out that this is just one factor, and that the combined effects of various processes in the milk at that temperature contribute to the sweeter flavour.

Now we have outlined the intermolecular forces, I would like to discuss how they come into play in my own research.

My work revolves around the synthesis of fluorescent molecules for use in OLEDs. These molecules can be polar, or non-polar. The current molecule I am building, is non-polar. These molecules function by exciting them with energy (from light or an electric current). When they are excited, electrons are move to different locations in the molecule, causing the molecule to vibrate in different ways. As the structure changes, it can become temporarily polar. This means it is then able to interact with a polar solvent. We say that like-dissolves-like. This is because of the interactions between polar molecules and a polar solvent, or non-polar molecules and a non-polar solvent. In my molecule, when it is excited, what was previously non-polar is now polar, so its relationship with the solvent changes. A “solvation shell” forms around the molecule, which works to change the vibronic nature of its energy and causes the colour of the light it emits to change. When an excited molecule relaxes back to its default state, it releases a photon of light. The bigger the difference in energy between the excited and relaxed states, the greater the energy of that photon – i.e. the more energetic, the bluer the light, the less energetic the redder the light (if you’re studying Higher Physics this should be familiar to you!). This process, the relationship between emission colour and the solvent, is known as solvatochromism. When my molecule is put into a polar solvent, the solvent interactions restrict its movements and absorb some of its energy, causing what is known as a redshift – its emitted photons have less energy. This is also known as a bathochromic shift. When put in a non-polar solvent, this effect is lessened, and the molecule is able to emit light with greater energy – causing what is called as a blueshift – also known as ahypsochromic shift. These types of molecules allow the user to tailor the wavelengths of light emitted precisely. They can potentially be used as diagnostics for healthcare, or environmental pollution – different environmental conditions giving distinctly different emissions – or indeed in OLEDs – allowing a specific colour of light to be specified during manufacture.

A fascinating paper was recently published by a research group at the University of Durham1 that exploited this effect in the solid state, effectively acting as a switch to turn fluorescence on and off. They took an emissive molecule and embedded it in a host material based on polyethylene oxide. This host material has the fascinating property that it can change its polarity depending upon its temperature. At high temperatures, the material is polar, and at lower temperatures, it is more non-polar. In polar conditions, the host material interacts with the emitter molecule and prevents the excited state from being able to relax via an emissive pathway – reducing the intensity of emissions. When cooled down, the material becomes non-polar, preventing interactions with the emitter and thereby enhancing the intensity of light given out.

So, intermolecular forces are NOT bonds, but rather electrostatic interactions between molecules that can hold them together. When you melt diamond, you break the covalent bonds between the atoms (very strong intramolecular interactions), which takes an enormous amount of energy, hence diamond’s very high melting point. When you melt ice, you are only working against the much weaker intermolecular forces – hydrogen bonds, so its melting point is significantly lower than diamond’s – much less with chloroform, which only has permanent dipole – permanent dipole interactions to work against – and even less with methane, which only has pathetically weak London Dispersal forces to overcome. In these cases, no covalent bonds are broken, so much less energy is required to change state.

References :

1 F. B. Dias, T. J. Penfold and A. P. Monkman, Photophysics of thermally activated delayed fluorescence molecules, Methods Appl. Fluoresc., 2017, 5, 012001.